A philosophy cafe is a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens to share their lived experiences as social beings, express opinions, and listen to others. Without disclosing their professions or positions, visitors to a philosophy cafe share personal experiences publicly, in a considered way. They do not use difficult specialized language. In these dialogues, it is crucial that participants listen without interrupting each other and feel secure that nothing they say will be dismissed outright. Participants use this space to assimilate and internalize the new perspectives that they gain, using them as a catalyst to reframe their own thinking. We established philosophy cafes in order to create spaces that make this possible.

There is a historical background behind the need for spaces like philosophy cafes. One reason is that as entities such as local community organizations and labor unions have ceased to function effectively as intermediaries between citizens and society, people have lost the ability to gather, shape public opinion, and voice their concerns about how society is run. Today, our involvement in politics is largely limited to casting a single vote in an election. Against this background, a new desire has emerged: the desire to think again for ourselves about the problems that we face and the solutions that might exist.

Disappointment in experts also underpins the spread of philosophy cafes. When the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster occurred after the Great East Japan Earthquake, almost no experts were able to offer comprehensive opinions that spanned disciplinary boundaries, and this fueled distrust in specialists. This sparked a burgeoning movement to think for ourselves rather than relying solely on experts. The issues addressed subsequently expanded to encompass issues including the destruction of the environment and climate change.

The real meaning of philosophy cafes lies in us discussing the problems we face ourselves, rather than leaving them to experts, by engaging in dialogue, bringing our mutual interests up against each other. What this represents is also an attempt to create public opinion starting from the smallest scale, against the background of the decline of entities that mediate between the individual and society more generally.

While people who attack others based on popular sentiment (“seron” in Japanese) are becoming increasingly common, few act based on public opinion (or “yoron”), and there are few spaces for such action. However, there are certainly people whose opinions correspond with public opinion and who wish to engage in relevant activities together with others. The significance of philosophy cafes also lies in how those who take up “yoron” through dialogue apply it within their own spheres of activity. Philosophy cafes serve as the initial stage in a series of processes leading to social action or political engagement, and can be considered as providing lessons in democracy.

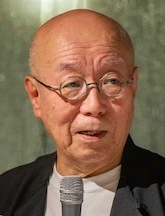

Professor Washida is a philosopher (Clinical Philosophy and Ethics). He completed doctoral studies at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Letters. He advocated for clinical philosophy and established the Clinical Philosophy Laboratory in the Graduate School of Letters while serving as a professor at Osaka University. He also served as President of Osaka University, President of Kyoto City University of Arts, and Director of Sendai Mediatheque. Professor Washida is the author of numerous works. He received the Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities for two books: Bunsan suru risei (“Dispersed Reason”) (Keiso Shobo) and Mōdo no meikyū (“The Labyrinth of Fashion”) (Chuo Koronsha). He received the Kuwabara Takeo Academic Prize for ‘Kiku’ koto no chikara (“The Power of Listening”) (TBS Britannica), the Yomiuri Prize for Literature for Guzuguzu no riyu (“Reasoning Japanese Onomatopeia”) (Kadokawa Gakugei Publishing), and the Watsuji Tetsuro Prize for Culture for Shoyū-ron (“The Theory of Property”) (Kodansha). He also supervised the publication of Tetsugaku kafe no tsukuri-kata (“How to Create a Philosophy Cafe”) (Osaka University Press).

Part of the appeal of philosophical dialogue lies in how its organizers shape it differently. My approach is that everyone has their own philosophy, and that we should work together to create a space where we can express those philosophies and listen to each other. I prioritize the attitude of “listening, waiting, and trusting” over skills or knowledge, making it accessible to anyone. I avoid terms like “facilitator” or “rules.” Rather than trying to manage the space in order to produce something, my presence there is as “someone who is there to listen.”

The thing that is important from my perspective is that all participants listen to each other’s “questions.” I encourage people to voice the murky feelings simmering inside them—anxiety, suffering, curiosity, anger—even if there is no order to them. That is what questions are. Questions connect participants because questions reveal the vulnerability of not knowing, they are a resistance, and they reach out for connection with others.

Rather than abruptly asking, “Are you for or against the death penalty?” or “Should we possess nuclear weapons?,” we begin with fundamental questions like “What does it fundamentally mean to atone?” or “We say possessing nuclear weapons makes a country strong, but what does it fundamentally mean to be a strong country?” This approach allows dialogue to unfold even when opinions differ. Through dialogue, we transcend the simple binary opposition of for or against. We come to recognize, even if only partially, the correspondences between ourselves and others, and learn to inhabit that complexity. This is the significance of dialogue and why it is an endeavor that builds trust in others and in society.

In daily life, we tend to see people through symbols like “teacher” or “department manager” – labels based on roles or attributes. But this carries the danger of dehumanizing people. Viewing others through such dehumanizing symbols is a direct path to war and genocide. Dialogue is time and experience spent engaging with people in ways that transcend symbolization. In dialogue, people emerge as individual humans stripped of their titles. Without resorting to violence in response to things that we don’t want to hear, we persist and we tolerate, listening to each other's “questions,” nurturing a language together. Dialogue is an endeavor that demands persistence.

Today's society is far too lacking in spaces for mutual listening. I worry that philosophical dialogue is popular merely as a fad. After each of my dialogue sessions, I suggest to participants that next time they might create a space for dialogue themselves. Why are such spaces so rare, despite the need of so many people for dialogue? It doesn't have to be philosophical dialogue; book clubs or welfare meetings are fine too. It is essential that we increase the number of spaces in which we are able to readily come together for mutual listening.

Ms. Nagai creates spaces for mutual listening and thinking through dialogue across Japan—in schools, companies, museums, shelters, and on the streets. Her initiatives include working to deepen philosophical dialogue, holding “Ozu Ozu Dialogues,” which attempt to explore politics and society, and the “Sensoutte?” project with photographer Yagi Saki, which uses artistic expression to spur dialogue about war. She is the author of Suichū no tetsugakusha-tachi (“The Philosophers in the Water”) (Shobunsha), Sekai no tekisetsu na hozon (“The Proper Preservation of the World”) (Kodansha), Samishikute gomen (“Sorry for Being Lonely”) (Yamato Shobo), and Kore ga sō nanoka (“Is This It?”) (Shueisha). She was the recipient of the 17th “Watakushi, Tsumari Nobody” Award.

My career began with philosophical dialogues with students at so-called “schools facing educational challenges.” I quickly realized that many of these children weren't incapable of learning; they simply lacked opportunities due to caring for parents or their own school refusal. Dialogues with children who had lived in environments forcing them to grapple with life's complexities yielded a diverse range of questions. Why must we go to school? Is studying really necessary? They carried these questions but lacked the chance to ponder them. After continuing these weekly philosophical dialogues for about five years, some students even advanced to universities known for rigorous scholarly standards. While university admission is a visible outcome, the core change lies in the children finding their voice and learning to trust their own thoughts and their own words.

Adults undergo similar transformations. In recent years, executives from large corporations grappling with challenges such as generating innovation and developing human resources have increasingly requested “philosophical dialogue for adults” sessions in the business setting. Many business professionals excel at problem-solving thinking—asking HOW—but struggle to formulate the fundamental questions of WHY and WHAT. Even if you start with the question “What is success, fundamentally?” the conversation will become “How can we achieve success?” Philosophy involves continuously thinking critically about meaning and concepts. There is no single correct answer, and no incorrect response, meaning that everyone is on an equal footing when faced with philosophical questions. Gradually the atmosphere within the dialogue transforms into one in which the participants want to think, and so ask questions, enabling discussions about the “fundamentals.” This shift in communication eventually transforms the organization. That is the true joy of philosophical dialogue in the business realm. Additionally, many business professionals are also central actors in influencing voting behavior in elections. We can expect that their transformation through philosophical dialogue will contribute to realizing a more inclusive and democratic society.

Academic philosophy, too, must encounter new forms of knowledge and thus change. For instance, engineers developing cameras may not be well-versed in photographic theory within philosophy, while at the same time, philosophers themselves remain unaware of the knowledge possessed by the engineering thinkers engaged in development work. Rather than philosophy occupying a position at the top of a hierarchy and disseminating insights downward, philosophers must now confront the imperative to incorporate and examine the tacit knowledge and the embodied knowledge involved in practical activity in the real world, thereby renewing philosophy itself. Embracing new forms of knowledge and evolving is the pursuit of true knowledge, and it is linked to the practice of democracy as a way of life.

Dr. Horikoshi’s research focuses on philosophical practice— the introduction of philosophical activities to school education and corporate/organizational settings—in addition to the philosophy of education. He holds a Ph.D. in Education from The University of Tokyo. He has been a Visiting Scholar at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, a Visiting Fellow in Sophia University's Institute of Global Concern, and a Visiting Fellow and Lecturer in Meiji University's Organization for the Strategic Coordination of Research and Intellectual Properties. He also serves as an advisor to multiple companies, consulting and conducting workshops utilizing “philosophical thinking.” His activities focus on how to apply philosophy in practical settings and how to connect philosophy to our daily lives. His publications include Tetsugaku wa kō tsukau (“How Philosophy Works”) (2020, Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha).

Osaka University's Center for the Study of CO* Design offers a shared program for graduate students that emphasizes dialogue. This stems from the fact that even graduate students in the same university, but from different disciplines, often struggle to understand each other. Someone unable to communicate with specialists from other fields could not possibly effectively engage with non-specialists to tackle societal problems. First, they must learn the etiquette of communicating with fellow graduate students from different disciplines.

In these classes, discussions between graduate students from different fields rarely converge easily. This is because they persist in debating without sufficient awareness of professional etiquette beyond the knowledge they have acquired. Only as the exchange continues and they become conscious of their differences and the origins of those differences do the students begin to recognize their own cognitive biases and truly grasp the values behind and the rationales of other ways of thinking. They also learn to relativize their own expertise and recognize others with differing perspectives as members of the same community who coexist with them.

However, coexistence—that is, accepting the existence of differing values—can sometimes impose a psychological burden. As demonstrated by the deep divisions arising as a result of various natural disasters, the Fukushima nuclear accident, and the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, people possess a tendency to believe their own choices are “correct” and others’ are wrong, precisely because these situations involve difficult decisions. Nevertheless, unless we pause somewhere, divisions will only deepen. We must avoid the danger of treating each other as incomprehensible others, rendering dialogue itself impossible.

The process of dialogue helps us to develop the “intellectual stamina” required to tolerate views that are incompatible with our own without deepening divisions. Rather than pursuing a single correct answer, carefully unraveling the divergences between our thinking through sustained dialogue builds the capacity to tolerate ambiguous situations where conflicting values coexist.

Increasing the amount of such dialogue also contributes to the formation and the maintenance of democracy. Democracy is created not only at a higher level beyond our reach, but also through the accumulation of small-scale efforts in daily life—understanding differing views through ongoing conversation. I hope to see more spaces like philosophy cafes emerge as venues for this “small politics” in everyday life.

Professor Yagi specializes in science and technology in society (STS) and human factors research. She engages in practical research focused on creating spaces for dialogue and collaboration among people with differing opinions and interests, for example in areas such as nuclear technology and climate change. She holds a Ph.D. in Engineering from Tohoku University. After serving in positions including as Associate Professor at the (then) Communication Design Center of Osaka University , she assumed her current position in 2020. She also serves as a Visiting Professor at the Open University of Japan. Professor Yagi holds numerous public positions, including as a member of the Subcommittee on Specified Radioactive Waste. Her publications include Taiwa no ba o dezain suru (“Designing Spaces for Dialogue”), Zoku: Taiwa no ba o dezain suru (“Designing Spaces for Dialogue: Part Two”) (both published by Osaka University Press), and Risuku shakai ni okeru shimin sanka (“Citizen Participation in A Risk Society”) (2021, The Society for the Promotion of the Open University of Japan), among numerous others.

For a long time I have organized citizen-participatory art festivals in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture. One initiative introduced during these festivals was a philosophy cafe. During the pandemic, when many activities were restricted, opportunities for face-to-face conversation became scarce, and there was demand from people seeking connection. The ‘Adult Philosophy Café’ I currently hold in Musashi-Shinjo focuses not on philosophy as one of the liberal arts, but on everyday topics. Each session explores a single theme—such as “What is love?”, “Difficulties in living”, or “Social sanctions”—where participants think together, speak freely, and collectively seek the meaning of living alongside others.

Philosophy cafes serve as a social mechanism, offering casual learning and the ability to develop a certain level of human connection to the community. They transcend generations, genders, and nationalities, offering a space for dialogue where people from diverse backgrounds are able to share their experiences, values, and thoughts around a single theme, even if they have never met before. I believe their significance lies in the experience of deepening both understanding of others and self-understanding. During these dialogues, moments emerge where the background to a speaker's beliefs becomes visible, allowing us to understand why they hold those beliefs. There are moments when the speakers themselves gain new insight into their own thoughts simply by articulating them. When this understanding of self and others clicks into place – that experience of “Ah, now I get it” – participants feel glad to have come, and want to come again. The philosophy cafe is a place where you can learn casually by listening to others, and also a happy place where your own words are listened to attentively.

In contemporary Japanese society, there is a strong tendency to avoid discussion of politics, religion, and similarly sensitive topics in everyday life. Opportunities to discuss topics that are difficult to broach with friends or colleagues, but which one still wishes to explore, are therefore quite rare. The ease offered by deepening dialogue on specific themes without necessarily deepening the interpersonal relationship itself seems to align well with the needs of modern people. The cafe is also a space that is accessible to those who struggle with building social connections and to older men who find community involvement burdensome. However, if someone gets out of hand and starts an argument, other participants may experience hurt, making the facilitator’s skill essential.

For instance, even in political contexts, it is dialogue rather than jeering or heckling that forms the foundation of democracy. Through dialogue, negative perceptions of politics can be dispelled, allowing citizens to choose trustworthy politicians and engage with the administration. Rather than treating politics and diplomacy solely as arenas for balancing interests, it is important to cultivate public spaces within society that foster deeper, more fundamental discussions about policy and politics. Philosophy cafes could serve as catalysts for fostering such dialogue.

Since the 2000s, Ms. Yokoi has launched numerous citizen-participation projects using art as an entry point. Starting in 2020, she began hosting philosophy cafes for adults and children, as well as reading groups exploring the works of political philosopher Hannah Arendt, in Kawasaki City. She is also actively involved in the community through other initiatives, including the participatory art festival 'Machinaka Art,' the philosophy and music salon 'TETSU-ON SALON,' and dementia cafes. She graduated with a major in handicrafts from the Department of Industrial Design, College of Art and Design, JOSHIBI College of Art and Design. Ms. Yokoi studied metal engraving at the Akasaka Jewelry Engraving Academy. After working at a jewelry manufacturer, she established her own studio, Atelier Sistermoon.

Throughout Japan, we are today seeing a renewed surge in the activity of “philosophy cafes.” The concept itself originated in Paris in 1992, with philosopher Marc Sautet's “Café for Socrates” events being particularly well-known. In the case of these events, people gathered at a café in the Place de la Bastille at 11 a.m. on Sundays to discuss diverse themes alongside philosophers. This signified the liberation of philosophy from the ivory tower, providing ordinary citizens an opportunity to discuss their interests in their own words.

Such philosophy cafes were introduced at an early stage in Japan, and a variety of related initiatives have since been put into practice. What is interesting is that philosophy cafes have not only taken root in Japanese society but are also developing further with the participation of residents at the local level. Perhaps in this, we can also make out the challenges faced by local communities and broader transformations in society. In an era in which dialogue is diminishing and social divisions are widening in our local communities, it is to be hoped that philosophy cafes will open up new possibilities. This edition of My Vision is titled “The Expansion of Philosophy Cafes Throughout Japan’s Local Communities,” and seeks to share the voices of academics and civic intellectuals engaged in diverse practices in this area.

Philosopher Kiyokazu Washida, who introduced philosophy cafes to Japan at an early stage and has organized them at institutions including Osaka University, defines them as “a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens to share their lived experiences as social beings, express opinions, and listen to others.” He points out that this movement stems from the declining function of entities that mediate between the individual and society such as local community organizations and labor unions, and tells us that now more than ever, “an attempt to create public opinion starting from the smallest scale” is needed.

Writer Rei Nagai emphasizes the importance of listening in philosophical dialogue. What matters, she tells us, is that “all participants listen to each other's ‘questions.’” She explains, “questions reveal the vulnerability of not knowing, they are a resistance, and they reach out for connection with others.” When discussing a subject like the death penalty, for example, rather than immediately asking whether participants are “for” or “against,” dialogue should proceed from fundamental questions such as “What does it really mean to atone?” Ms. Nagai argues that the significance of dialogue lies in recognizing “even if only partially, the correspondences between ourselves and others, and learn[ing] to inhabit that complexity”

Yosuke Horikoshi of the University of Tokyo's Uehiro Research Division for the Philosophy of Coexistence points out, based on his experience at so-called “schools facing educational challenges,” that many children with poor academic records are not incapable of learning; they have simply never had the opportunity to learn. He reports that through persistent dialogue on questions like “Is studying really necessary?,” “the children [found] their voice and [learnt] to trust their own thoughts and their own words.” Changes in communication also bring about transformation in organizations. It goes without saying that academic philosophy must also change.

At Osaka University, dialogue sessions are integrated into graduate-level core education programs. Ekou Yagi of the university’s Center for the Study of CO* Design indicates, “Someone unable to communicate with specialists from other fields could not possibly effectively engage with non-specialists to tackle societal problems.” People tend to believe their own choices are correct and all others are wrong. We need to cultivate the “intellectual stamina” required to tolerate differing perspectives and prevent divisions from deepening.

Fumie Yokoi, also known as Catherine, has been an organizer of participatory art festivals from the perspective of ordinary citizens. She currently runs an “Adult Philosophy Cafe” in Musashi-Shinjo, Kawasaki City. Among friends and colleagues, opportunities for dialogue that delves into each other’s values are rare. Ms. Yokoi offers the valuable insight that “deepening dialogue on specific themes without necessarily deepening the interpersonal relationship itself seems to align well with the needs of modern people.” Ms. Yokoi emphasizes that participation in philosophy cafes can also lead to participants choosing the politicians that they feel to be most trustworthy and engaging with the administration.

As the functions of traditional intermediary groups like local community organizations and labor unions decline, the opportunities for dialogue that should form the foundation of democracy seem to be disappearing unbeknownst to us. Dialogue isn't merely a matter of those with knowledge presenting their views. What we need now are spaces in which individuals can give voice to their unspoken anxieties and frustrations—spaces in which they aren't immediately asked whether they are “for or against,” but can instead explore more fundamental questions about the essence of things and be heard. Against this background, it is possible that philosophy cafes are becoming a new circuit for contemporary politics.

Professor Uno is an Executive Vice President of NIRA and a Professor at The University of Tokyo's Institute of Social Science. He holds a Ph.D. in Law from The University of Tokyo's Graduate Schools for Law and Politics and specializes in the history of Western political thought and political philosophy.

Interview period:October - November, 2025

Interviewer :Yoshie Udagawa (Research Coordinator & Research Fellow, NIRA)

Editors (Japanese): Reiko Kanda, Maiko Sakaki, Kazuko Kawamoto and Tatsuya Yamaji

Editor (English): Chiharu Hagi

Translation: Michael Faul

This is a translation of a paper originally published in Japanese. NIRA bears full responsibility for the translation presented here.

Kiyokazu Washida Philosopher / Professor Emeritus, Osaka UniversityA philosophy cafe is a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens...

Kiyokazu Washida Philosopher / Professor Emeritus, Osaka UniversityA philosophy cafe is a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens... Rei Nagai WriterPart of the appeal of philosophical dialogue lies in how its organizers shape it differently. My approach...

Rei Nagai WriterPart of the appeal of philosophical dialogue lies in how its organizers shape it differently. My approach... Yosuke Horikoshi Research Fellow, Uehiro Research Division for the Philosophy of Coexistence, The University of Tokyo Center for PhilosophyMy career began with philosophical dialogues with students at so-called “schools facing educational...

Yosuke Horikoshi Research Fellow, Uehiro Research Division for the Philosophy of Coexistence, The University of Tokyo Center for PhilosophyMy career began with philosophical dialogues with students at so-called “schools facing educational... Ekou Yagi Professor, Center for the Study of CO* Design, Osaka UniversityOsaka University's Center for the Study of CO* Design offers a shared program for graduate students...

Ekou Yagi Professor, Center for the Study of CO* Design, Osaka UniversityOsaka University's Center for the Study of CO* Design offers a shared program for graduate students... Fumie Yokoi (Catherine) Director, Atelier SistermoonFor a long time I have organized citizen-participatory art festivals in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa...

Fumie Yokoi (Catherine) Director, Atelier SistermoonFor a long time I have organized citizen-participatory art festivals in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa...

expert opinions

01

Democracy Flourishes in Spaces Where Differing Opinions Can Be Expressed with Confidence

Democracy Flourishes in Spaces Where Differing Opinions Can Be Expressed with Confidence

Kiyokazu Washida Philosopher / Professor Emeritus, Osaka University

A philosophy cafe is a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens to share their lived experiences as social beings, express opinions, and listen to others. Without disclosing their professions or positions, visitors to a philosophy cafe share personal experiences publicly, in a considered way. They do not use difficult specialized language. In these dialogues, it is crucial that participants listen without interrupting each other and feel secure that nothing they say will be dismissed outright. Participants use this space to assimilate and internalize the new perspectives that they gain, using them as a catalyst to reframe their own thinking. We established philosophy cafes in order to create spaces that make this possible.

There is a historical background behind the need for spaces like philosophy cafes. One reason is that as entities such as local community organizations and labor unions have ceased to function effectively as intermediaries between citizens and society, people have lost the ability to gather, shape public opinion, and voice their concerns about how society is run. Today, our involvement in politics is largely limited to casting a single vote in an election. Against this background, a new desire has emerged: the desire to think again for ourselves about the problems that we face and the solutions that might exist.

Disappointment in experts also underpins the spread of philosophy cafes. When the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster occurred after the Great East Japan Earthquake, almost no experts were able to offer comprehensive opinions that spanned disciplinary boundaries, and this fueled distrust in specialists. This sparked a burgeoning movement to think for ourselves rather than relying solely on experts. The issues addressed subsequently expanded to encompass issues including the destruction of the environment and climate change.

The real meaning of philosophy cafes lies in us discussing the problems we face ourselves, rather than leaving them to experts, by engaging in dialogue, bringing our mutual interests up against each other. What this represents is also an attempt to create public opinion starting from the smallest scale, against the background of the decline of entities that mediate between the individual and society more generally.

While people who attack others based on popular sentiment (“seron” in Japanese) are becoming increasingly common, few act based on public opinion (or “yoron”), and there are few spaces for such action. However, there are certainly people whose opinions correspond with public opinion and who wish to engage in relevant activities together with others. The significance of philosophy cafes also lies in how those who take up “yoron” through dialogue apply it within their own spheres of activity. Philosophy cafes serve as the initial stage in a series of processes leading to social action or political engagement, and can be considered as providing lessons in democracy.

Professor Washida is a philosopher (Clinical Philosophy and Ethics). He completed doctoral studies at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Letters. He advocated for clinical philosophy and established the Clinical Philosophy Laboratory in the Graduate School of Letters while serving as a professor at Osaka University. He also served as President of Osaka University, President of Kyoto City University of Arts, and Director of Sendai Mediatheque. Professor Washida is the author of numerous works. He received the Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities for two books: Bunsan suru risei (“Dispersed Reason”) (Keiso Shobo) and Mōdo no meikyū (“The Labyrinth of Fashion”) (Chuo Koronsha). He received the Kuwabara Takeo Academic Prize for ‘Kiku’ koto no chikara (“The Power of Listening”) (TBS Britannica), the Yomiuri Prize for Literature for Guzuguzu no riyu (“Reasoning Japanese Onomatopeia”) (Kadokawa Gakugei Publishing), and the Watsuji Tetsuro Prize for Culture for Shoyū-ron (“The Theory of Property”) (Kodansha). He also supervised the publication of Tetsugaku kafe no tsukuri-kata (“How to Create a Philosophy Cafe”) (Osaka University Press).

02

“Fundamental Questions” and “Spaces for Mutual Listening” Build Trust

“Fundamental Questions” and “Spaces for Mutual Listening” Build Trust

Rei Nagai Writer

Part of the appeal of philosophical dialogue lies in how its organizers shape it differently. My approach is that everyone has their own philosophy, and that we should work together to create a space where we can express those philosophies and listen to each other. I prioritize the attitude of “listening, waiting, and trusting” over skills or knowledge, making it accessible to anyone. I avoid terms like “facilitator” or “rules.” Rather than trying to manage the space in order to produce something, my presence there is as “someone who is there to listen.”

The thing that is important from my perspective is that all participants listen to each other’s “questions.” I encourage people to voice the murky feelings simmering inside them—anxiety, suffering, curiosity, anger—even if there is no order to them. That is what questions are. Questions connect participants because questions reveal the vulnerability of not knowing, they are a resistance, and they reach out for connection with others.

Rather than abruptly asking, “Are you for or against the death penalty?” or “Should we possess nuclear weapons?,” we begin with fundamental questions like “What does it fundamentally mean to atone?” or “We say possessing nuclear weapons makes a country strong, but what does it fundamentally mean to be a strong country?” This approach allows dialogue to unfold even when opinions differ. Through dialogue, we transcend the simple binary opposition of for or against. We come to recognize, even if only partially, the correspondences between ourselves and others, and learn to inhabit that complexity. This is the significance of dialogue and why it is an endeavor that builds trust in others and in society.

In daily life, we tend to see people through symbols like “teacher” or “department manager” – labels based on roles or attributes. But this carries the danger of dehumanizing people. Viewing others through such dehumanizing symbols is a direct path to war and genocide. Dialogue is time and experience spent engaging with people in ways that transcend symbolization. In dialogue, people emerge as individual humans stripped of their titles. Without resorting to violence in response to things that we don’t want to hear, we persist and we tolerate, listening to each other's “questions,” nurturing a language together. Dialogue is an endeavor that demands persistence.

Today's society is far too lacking in spaces for mutual listening. I worry that philosophical dialogue is popular merely as a fad. After each of my dialogue sessions, I suggest to participants that next time they might create a space for dialogue themselves. Why are such spaces so rare, despite the need of so many people for dialogue? It doesn't have to be philosophical dialogue; book clubs or welfare meetings are fine too. It is essential that we increase the number of spaces in which we are able to readily come together for mutual listening.

Ms. Nagai creates spaces for mutual listening and thinking through dialogue across Japan—in schools, companies, museums, shelters, and on the streets. Her initiatives include working to deepen philosophical dialogue, holding “Ozu Ozu Dialogues,” which attempt to explore politics and society, and the “Sensoutte?” project with photographer Yagi Saki, which uses artistic expression to spur dialogue about war. She is the author of Suichū no tetsugakusha-tachi (“The Philosophers in the Water”) (Shobunsha), Sekai no tekisetsu na hozon (“The Proper Preservation of the World”) (Kodansha), Samishikute gomen (“Sorry for Being Lonely”) (Yamato Shobo), and Kore ga sō nanoka (“Is This It?”) (Shueisha). She was the recipient of the 17th “Watakushi, Tsumari Nobody” Award.

03

Philosophical Dialogue Cultivates Change in Awareness in Educational Settings and Business Organizations

Philosophical Dialogue Cultivates Change in Awareness in Educational Settings and Business Organizations

Yosuke Horikoshi Research Fellow, Uehiro Research Division for the Philosophy of Coexistence, The University of Tokyo Center for Philosophy

My career began with philosophical dialogues with students at so-called “schools facing educational challenges.” I quickly realized that many of these children weren't incapable of learning; they simply lacked opportunities due to caring for parents or their own school refusal. Dialogues with children who had lived in environments forcing them to grapple with life's complexities yielded a diverse range of questions. Why must we go to school? Is studying really necessary? They carried these questions but lacked the chance to ponder them. After continuing these weekly philosophical dialogues for about five years, some students even advanced to universities known for rigorous scholarly standards. While university admission is a visible outcome, the core change lies in the children finding their voice and learning to trust their own thoughts and their own words.

Adults undergo similar transformations. In recent years, executives from large corporations grappling with challenges such as generating innovation and developing human resources have increasingly requested “philosophical dialogue for adults” sessions in the business setting. Many business professionals excel at problem-solving thinking—asking HOW—but struggle to formulate the fundamental questions of WHY and WHAT. Even if you start with the question “What is success, fundamentally?” the conversation will become “How can we achieve success?” Philosophy involves continuously thinking critically about meaning and concepts. There is no single correct answer, and no incorrect response, meaning that everyone is on an equal footing when faced with philosophical questions. Gradually the atmosphere within the dialogue transforms into one in which the participants want to think, and so ask questions, enabling discussions about the “fundamentals.” This shift in communication eventually transforms the organization. That is the true joy of philosophical dialogue in the business realm. Additionally, many business professionals are also central actors in influencing voting behavior in elections. We can expect that their transformation through philosophical dialogue will contribute to realizing a more inclusive and democratic society.

Academic philosophy, too, must encounter new forms of knowledge and thus change. For instance, engineers developing cameras may not be well-versed in photographic theory within philosophy, while at the same time, philosophers themselves remain unaware of the knowledge possessed by the engineering thinkers engaged in development work. Rather than philosophy occupying a position at the top of a hierarchy and disseminating insights downward, philosophers must now confront the imperative to incorporate and examine the tacit knowledge and the embodied knowledge involved in practical activity in the real world, thereby renewing philosophy itself. Embracing new forms of knowledge and evolving is the pursuit of true knowledge, and it is linked to the practice of democracy as a way of life.

Dr. Horikoshi’s research focuses on philosophical practice— the introduction of philosophical activities to school education and corporate/organizational settings—in addition to the philosophy of education. He holds a Ph.D. in Education from The University of Tokyo. He has been a Visiting Scholar at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, a Visiting Fellow in Sophia University's Institute of Global Concern, and a Visiting Fellow and Lecturer in Meiji University's Organization for the Strategic Coordination of Research and Intellectual Properties. He also serves as an advisor to multiple companies, consulting and conducting workshops utilizing “philosophical thinking.” His activities focus on how to apply philosophy in practical settings and how to connect philosophy to our daily lives. His publications include Tetsugaku wa kō tsukau (“How Philosophy Works”) (2020, Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha).

04

Building “Intellectual Stamina” Through Dialogue to Tolerate Situations Where Differing Values Coexist

Building “Intellectual Stamina” Through Dialogue to Tolerate Situations Where Differing Values Coexist

Ekou Yagi Professor, Center for the Study of CO* Design, Osaka University

Osaka University's Center for the Study of CO* Design offers a shared program for graduate students that emphasizes dialogue. This stems from the fact that even graduate students in the same university, but from different disciplines, often struggle to understand each other. Someone unable to communicate with specialists from other fields could not possibly effectively engage with non-specialists to tackle societal problems. First, they must learn the etiquette of communicating with fellow graduate students from different disciplines.

In these classes, discussions between graduate students from different fields rarely converge easily. This is because they persist in debating without sufficient awareness of professional etiquette beyond the knowledge they have acquired. Only as the exchange continues and they become conscious of their differences and the origins of those differences do the students begin to recognize their own cognitive biases and truly grasp the values behind and the rationales of other ways of thinking. They also learn to relativize their own expertise and recognize others with differing perspectives as members of the same community who coexist with them.

However, coexistence—that is, accepting the existence of differing values—can sometimes impose a psychological burden. As demonstrated by the deep divisions arising as a result of various natural disasters, the Fukushima nuclear accident, and the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, people possess a tendency to believe their own choices are “correct” and others’ are wrong, precisely because these situations involve difficult decisions. Nevertheless, unless we pause somewhere, divisions will only deepen. We must avoid the danger of treating each other as incomprehensible others, rendering dialogue itself impossible.

The process of dialogue helps us to develop the “intellectual stamina” required to tolerate views that are incompatible with our own without deepening divisions. Rather than pursuing a single correct answer, carefully unraveling the divergences between our thinking through sustained dialogue builds the capacity to tolerate ambiguous situations where conflicting values coexist.

Increasing the amount of such dialogue also contributes to the formation and the maintenance of democracy. Democracy is created not only at a higher level beyond our reach, but also through the accumulation of small-scale efforts in daily life—understanding differing views through ongoing conversation. I hope to see more spaces like philosophy cafes emerge as venues for this “small politics” in everyday life.

Professor Yagi specializes in science and technology in society (STS) and human factors research. She engages in practical research focused on creating spaces for dialogue and collaboration among people with differing opinions and interests, for example in areas such as nuclear technology and climate change. She holds a Ph.D. in Engineering from Tohoku University. After serving in positions including as Associate Professor at the (then) Communication Design Center of Osaka University , she assumed her current position in 2020. She also serves as a Visiting Professor at the Open University of Japan. Professor Yagi holds numerous public positions, including as a member of the Subcommittee on Specified Radioactive Waste. Her publications include Taiwa no ba o dezain suru (“Designing Spaces for Dialogue”), Zoku: Taiwa no ba o dezain suru (“Designing Spaces for Dialogue: Part Two”) (both published by Osaka University Press), and Risuku shakai ni okeru shimin sanka (“Citizen Participation in A Risk Society”) (2021, The Society for the Promotion of the Open University of Japan), among numerous others.

05

A Diverse Variety of People From the Community Freely Conversing on a Single Theme

A Diverse Variety of People From the Community Freely Conversing on a Single Theme

Fumie Yokoi (Catherine) Director, Atelier Sistermoon

For a long time I have organized citizen-participatory art festivals in Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture. One initiative introduced during these festivals was a philosophy cafe. During the pandemic, when many activities were restricted, opportunities for face-to-face conversation became scarce, and there was demand from people seeking connection. The ‘Adult Philosophy Café’ I currently hold in Musashi-Shinjo focuses not on philosophy as one of the liberal arts, but on everyday topics. Each session explores a single theme—such as “What is love?”, “Difficulties in living”, or “Social sanctions”—where participants think together, speak freely, and collectively seek the meaning of living alongside others.

Philosophy cafes serve as a social mechanism, offering casual learning and the ability to develop a certain level of human connection to the community. They transcend generations, genders, and nationalities, offering a space for dialogue where people from diverse backgrounds are able to share their experiences, values, and thoughts around a single theme, even if they have never met before. I believe their significance lies in the experience of deepening both understanding of others and self-understanding. During these dialogues, moments emerge where the background to a speaker's beliefs becomes visible, allowing us to understand why they hold those beliefs. There are moments when the speakers themselves gain new insight into their own thoughts simply by articulating them. When this understanding of self and others clicks into place – that experience of “Ah, now I get it” – participants feel glad to have come, and want to come again. The philosophy cafe is a place where you can learn casually by listening to others, and also a happy place where your own words are listened to attentively.

In contemporary Japanese society, there is a strong tendency to avoid discussion of politics, religion, and similarly sensitive topics in everyday life. Opportunities to discuss topics that are difficult to broach with friends or colleagues, but which one still wishes to explore, are therefore quite rare. The ease offered by deepening dialogue on specific themes without necessarily deepening the interpersonal relationship itself seems to align well with the needs of modern people. The cafe is also a space that is accessible to those who struggle with building social connections and to older men who find community involvement burdensome. However, if someone gets out of hand and starts an argument, other participants may experience hurt, making the facilitator’s skill essential.

For instance, even in political contexts, it is dialogue rather than jeering or heckling that forms the foundation of democracy. Through dialogue, negative perceptions of politics can be dispelled, allowing citizens to choose trustworthy politicians and engage with the administration. Rather than treating politics and diplomacy solely as arenas for balancing interests, it is important to cultivate public spaces within society that foster deeper, more fundamental discussions about policy and politics. Philosophy cafes could serve as catalysts for fostering such dialogue.

Since the 2000s, Ms. Yokoi has launched numerous citizen-participation projects using art as an entry point. Starting in 2020, she began hosting philosophy cafes for adults and children, as well as reading groups exploring the works of political philosopher Hannah Arendt, in Kawasaki City. She is also actively involved in the community through other initiatives, including the participatory art festival 'Machinaka Art,' the philosophy and music salon 'TETSU-ON SALON,' and dementia cafes. She graduated with a major in handicrafts from the Department of Industrial Design, College of Art and Design, JOSHIBI College of Art and Design. Ms. Yokoi studied metal engraving at the Akasaka Jewelry Engraving Academy. After working at a jewelry manufacturer, she established her own studio, Atelier Sistermoon.

about this issue

The Expansion of Philosophy Cafes Throughout Japan’s Local Communities

- New Political Circuits Emerging From New Spaces for Dialogue

The Expansion of Philosophy Cafes Throughout Japan’s Local Communities

- New Political Circuits Emerging From New Spaces for Dialogue

Shigeki Uno Executive Vice President, NIRA / Professor, Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo

Throughout Japan, we are today seeing a renewed surge in the activity of “philosophy cafes.” The concept itself originated in Paris in 1992, with philosopher Marc Sautet's “Café for Socrates” events being particularly well-known. In the case of these events, people gathered at a café in the Place de la Bastille at 11 a.m. on Sundays to discuss diverse themes alongside philosophers. This signified the liberation of philosophy from the ivory tower, providing ordinary citizens an opportunity to discuss their interests in their own words.

Such philosophy cafes were introduced at an early stage in Japan, and a variety of related initiatives have since been put into practice. What is interesting is that philosophy cafes have not only taken root in Japanese society but are also developing further with the participation of residents at the local level. Perhaps in this, we can also make out the challenges faced by local communities and broader transformations in society. In an era in which dialogue is diminishing and social divisions are widening in our local communities, it is to be hoped that philosophy cafes will open up new possibilities. This edition of My Vision is titled “The Expansion of Philosophy Cafes Throughout Japan’s Local Communities,” and seeks to share the voices of academics and civic intellectuals engaged in diverse practices in this area.

Questioning, Speaking, and Listening Together as Citizens of Society

Philosopher Kiyokazu Washida, who introduced philosophy cafes to Japan at an early stage and has organized them at institutions including Osaka University, defines them as “a space in which strangers, regardless of their specific attributes, gather as fellow citizens to share their lived experiences as social beings, express opinions, and listen to others.” He points out that this movement stems from the declining function of entities that mediate between the individual and society such as local community organizations and labor unions, and tells us that now more than ever, “an attempt to create public opinion starting from the smallest scale” is needed.

Writer Rei Nagai emphasizes the importance of listening in philosophical dialogue. What matters, she tells us, is that “all participants listen to each other's ‘questions.’” She explains, “questions reveal the vulnerability of not knowing, they are a resistance, and they reach out for connection with others.” When discussing a subject like the death penalty, for example, rather than immediately asking whether participants are “for” or “against,” dialogue should proceed from fundamental questions such as “What does it really mean to atone?” Ms. Nagai argues that the significance of dialogue lies in recognizing “even if only partially, the correspondences between ourselves and others, and learn[ing] to inhabit that complexity”

The Practice of Dialogue Advances in Diverse Settings

Yosuke Horikoshi of the University of Tokyo's Uehiro Research Division for the Philosophy of Coexistence points out, based on his experience at so-called “schools facing educational challenges,” that many children with poor academic records are not incapable of learning; they have simply never had the opportunity to learn. He reports that through persistent dialogue on questions like “Is studying really necessary?,” “the children [found] their voice and [learnt] to trust their own thoughts and their own words.” Changes in communication also bring about transformation in organizations. It goes without saying that academic philosophy must also change.

At Osaka University, dialogue sessions are integrated into graduate-level core education programs. Ekou Yagi of the university’s Center for the Study of CO* Design indicates, “Someone unable to communicate with specialists from other fields could not possibly effectively engage with non-specialists to tackle societal problems.” People tend to believe their own choices are correct and all others are wrong. We need to cultivate the “intellectual stamina” required to tolerate differing perspectives and prevent divisions from deepening.

Fumie Yokoi, also known as Catherine, has been an organizer of participatory art festivals from the perspective of ordinary citizens. She currently runs an “Adult Philosophy Cafe” in Musashi-Shinjo, Kawasaki City. Among friends and colleagues, opportunities for dialogue that delves into each other’s values are rare. Ms. Yokoi offers the valuable insight that “deepening dialogue on specific themes without necessarily deepening the interpersonal relationship itself seems to align well with the needs of modern people.” Ms. Yokoi emphasizes that participation in philosophy cafes can also lead to participants choosing the politicians that they feel to be most trustworthy and engaging with the administration.

A New Circuit for Politics in the Modern Age

As the functions of traditional intermediary groups like local community organizations and labor unions decline, the opportunities for dialogue that should form the foundation of democracy seem to be disappearing unbeknownst to us. Dialogue isn't merely a matter of those with knowledge presenting their views. What we need now are spaces in which individuals can give voice to their unspoken anxieties and frustrations—spaces in which they aren't immediately asked whether they are “for or against,” but can instead explore more fundamental questions about the essence of things and be heard. Against this background, it is possible that philosophy cafes are becoming a new circuit for contemporary politics.

Professor Uno is an Executive Vice President of NIRA and a Professor at The University of Tokyo's Institute of Social Science. He holds a Ph.D. in Law from The University of Tokyo's Graduate Schools for Law and Politics and specializes in the history of Western political thought and political philosophy.

Interview period:October - November, 2025

Interviewer :Yoshie Udagawa (Research Coordinator & Research Fellow, NIRA)

Editors (Japanese): Reiko Kanda, Maiko Sakaki, Kazuko Kawamoto and Tatsuya Yamaji

Editor (English): Chiharu Hagi

Translation: Michael Faul

This is a translation of a paper originally published in Japanese. NIRA bears full responsibility for the translation presented here.